The Affective Filter Hypothesis for Learning a Foreign Language

Read other articles:

Back to posts

Table of Contents

If you’re learning a foreign language and have never heard of Stephen Krashen, it’s time to get acquainted.

And if you’ve ever been asked to speak out in a foreign language when you didn’t feel comfortable doing so, it’s even more important to learn about Krashen’s theories.

As a leading light in language acquisition for the past several decades, Krashen’s teachings on how people learn languages are critical to learning your chosen language more efficiently and to a higher level.

Krashen’s “Affective Filter” hypothesis is one of five major language acquisition theories developed by the linguist but don’t worry about the fancy name; the concepts it refers to are quite straightforward.

Let’s take a closer look at the Affective Filter Hypothesis and how it could boost your language learning…

What is the Affective Filter?

Krashen’s Affective Filter Hypothesis refers to several variables related to the theory that negative attitudes and emotions can impede the ability to learn.

The term “Affective Filter” was first coined by Dulay and Burt (1977) but later adopted by Krashen in his work.

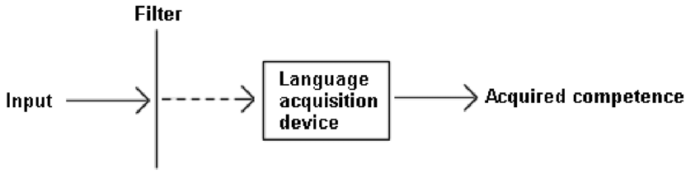

Affective means “referring to, arising from, or influencing feelings or emotions.” The “Affective Filter” may be seen as a psychological wall or gate that prevents input from being effectively processed in a learner’s mind, blocking cognition and inhibiting learning due to one’s mood or feelings at the time.

Conversely, in the right “mood” or state of mind, an individual’s emotions and personality can assist with language acquisition.

The Affective Filter can be high or low. The higher the filter, the more likely language learning will be impeded; the lower the filter, the more likely language learning will be successful.

To learn a language effectively, we need to be aware of the elements that prevent this from happening. The Affective Filter Hypothesis helps us identify these factors so that we’re more aware of them and can modify our learning experiences accordingly.

What are the main affective factors that make up the filter?

When we think about learning a language, we usually focus on qualities like skill level, memory, intelligence, patience, and perseverance.

Krashen points out that learning a new language is different from learning other subjects because it requires public practice. That means it has a high potential to embarrass a learner or cause anxiety and stress.

The Affective Filter Hypothesis, then, identifies three main categories of variables that play a role in second language learning:

- Motivation

- Self-confidence, and

- Anxiety

These factors (especially self-confidence and anxiety) are seldom part of the language-learning conversation.

Likewise, personality traits are not normally part of the discussion though an individual’s unique characteristics also play a role in language learning, according to Krashen. For instance, extrovert learners are generally better equipped for success in second language acquisition — and introverted learners are more likely to feel inhibited and impacted by an elevated Affective Filter.

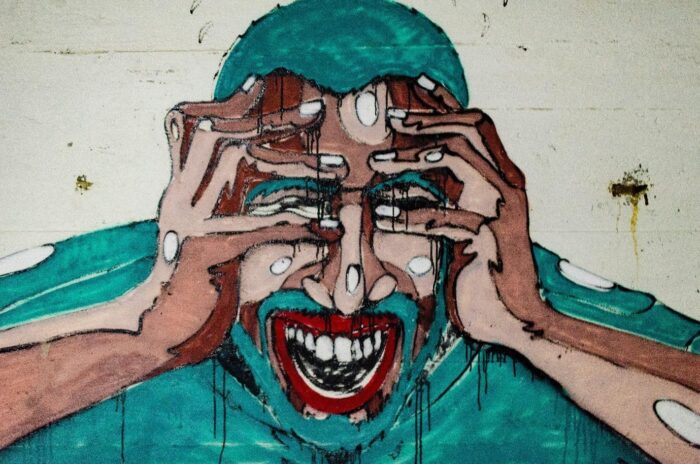

Krashen hypothesizes that when feelings of anxiety, fear or embarrassment are prominent for a learner, effective language acquisition cannot occur. The imaginary wall rises or the gate closes in the learner’s minds and obstructs effective learning.

Learners with low motivation, low self-confidence, and low self-esteem, along with a high level of anxiety are less likely to learn effectively.

Conversely, when a student feels safe, comfortable, and relaxed, the wall is lowered and language acquisition will occur naturally if the right stimuli are provided (namely, comprehensible input or input in the target language that is just above the learner’s current proficiency level).

Does the science back up the Affective Filter Hypothesis?

Krashen asserts that “for language acquisition to really succeed, anxiety should be zero.” But does the science agree?

During and after times of stress, hormones and neurotransmitters are released that affect us physically, mentally, and emotionally.

Some stress during the learning process is generally thought to enhance memory formation. However, it is also known to harm memory retrieval and stress is generally counterproductive when learning languages.

Anxiety is a common stress response. If we sense danger, our brains and bodies go into “survival” mode, alerted to the flood of messages that our bodies send us. Blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration rate may increase as the adrenaline and other neurochemicals pump through the body in response to the perceived danger.

This fear response can block or damage other parts of the brain responsible for cognition and learning.

The research on learning adds some useful insight.

In one 2018 study, researchers simulated a 15-minute job interview including a public speaking portion designed to raise stress levels. Fifteen minutes after this experience, participants were required to learn two different types of information: one related to memories they already held and the other to new information. Researchers noted that “stressed participants displayed aberrant functional connectivity between brain regions involved in schema processing when encoding novel information.”

Delving deep into the neuroscience of learning is beyond the scope of this article but, generally speaking, the science would seem to bear out Krashen’s Affective Filter Hypothesis.

How does this theory impact your language learning?

“The effective language teacher is someone who can provide input and help make it comprehensible in a low anxiety situation.”

Stephen Krashen

If you’re lucky enough to be able to pick up a language without ever needing to know any language acquisition theories, more power to you.

For the rest of us, understanding what makes us stressed or anxious, while becoming more aware of our own levels of motivation and self-esteem and what our learning preferences are can be of great use when we learn a foreign language.

If you’re aiming for a near-native-speaker level, you’ll need the best possible language learning methods to get there — rather than wasting your time with methods that don’t suit you.

Traditional foreign language instruction is based on output-heavy, teacher-led instruction, with regular testing and high pressure. In light of Krashen’s theories, does this seem conducive to a positive language-learning experience?

Or is there a better way to approach language acquisition?

Ultimately, how can you lower the affective filter and learn in an environment that is fully engaging, non-threatening, and motivational — yet effective at teaching the desired learning points?

Flashcards and the Affective Filter

Does the mere thought of a flashcard fill you with dread?

Using flashcards to test vocabulary recall is a common teaching method with second languages. It provides a controlled classroom method where only one person speaks at a time and progress is very measurable (most language programs love this).

But is it effective? The consensus seems to be that flashcards work because they promote active recall in your brain. But, looking at this method through Krashen’s eyes, flashcards fail for many learners.

Flashcards may be great for self-confident, extraverted language learners who are used to public speaking. For more introverted learners — even those who are highly motivated — this method may be a trigger for the Affective Filter to be raised.

The fear of making a mistake or looking stupid may cause the stress response to kick in with less confident learners — and learning becomes almost impossible.

What can language teachers do to lower the affective filter?

Krashen said this: “Language acquisition does not require extensive use of conscious grammatical rules, and does not require tedious drill”.

So, what does it require?

Teachers may want to pay attention to the three key elements of the Affective Filter identified by Krashen:

Motivation

Motivation may largely be controlled from “inside” each individual but teachers can influence motivation levels too — through choice, voice, and relevance.

If students can select topics of interest in the right “voice” that are relevant to their lives, they will become more “invested” in the process, which should increase motivation levels and lower the Affective Filter.

Self-confidence

Being more aware of learners’ confidence levels can help teachers tailor the language-learning experience to the needs of each student.

Creating a welcoming, non-threatening, supportive environment where language lessons are pitched at the right level (with “comprehensible input”) goes a long way to building confidence. If learners feel isolated, inhibited or inferior to other learners, the Affective Filter may be raised.

Anxiety

Lowering the threat of anxiety and recognizing which learners thrive or buckle under pressure is also part of a language teacher’s role. Constantly correcting mistakes and singling out individuals may not be the best approach.

Look to create a “safe” learning environment where risk-taking is seen as positive, mistakes are viewed as valuable learning opportunities, and learning is pitched at the right level to lower the affective filter. This will remove obstructions to effective learning. Forcing output too early or highlighting issues that can cause embarrassment are likely to be counterproductive.

Lower the Affective Filter by learning from video

Don’t let the Affective Filter sabotage your language learning efforts!

Learning a language with video is one of the most effective, anxiety-free ways to learn a language for motivated learners aspiring to a high level.

Video learning ticks many of the boxes that Stephen Krashen recommends for effective language acquisition. It can provide comprehensible input via compelling content in the target language and in a low-anxiety environment that prevents the Affective Filter from obstructing learning.

Our language learning app is inspired by the work of Krashen and can help you master a foreign language by watching subtitled YouTube video. It combines the best of AI with natural human learning methods so that your learning is convenient, at your own pace, motivational, and effective.

AI becomes your teacher as you immerse yourself in the target language and culture, learning in context and with visual as well as audio cues from the videos Try it now – it’s completely free!

Read other articles:

Back to posts